In the water column, meeting fish, jellyfish, and sea turtles

- A BIT EVERYWHERE AND OFTEN NEXT TO YOU

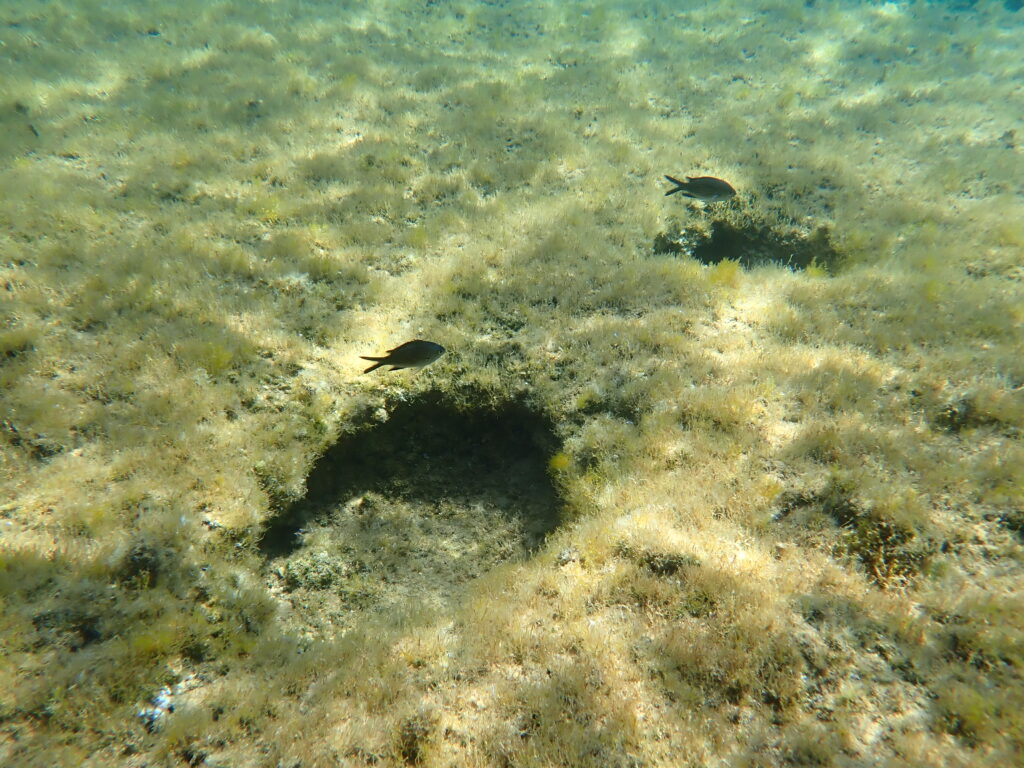

Saddled seabreams and damselfishes

The saddled seabream, Oblada melanura (Linnaeus, 1758) – Sparidae

Saddled breams are fusiform, silver in color, with a typical black saddle-shaped spot edged with white at the base of the caudal fin and a gray lateral line on each flank. The eyes are very large, close to the mouth. This one is terminal, oblique with corners pointing downwards which gives it a funny sulky air!

In shallow coastal waters their size is about 10-15 cm (offshore it can reach up to 50 cm). They live in small schools above rocky bottoms and seagrass beds, at depths usually ranging from the surface up to 30 m (they can migrate deeper in winter).

It is an opportunistic omnivore, capturing zooplankton, larvae, eggs, small crustaceans, or even grazing on sessile benthos (small animals or algae).

Saddled seabreams often follow the swimmer very closely… undoubtedly looking for small preys carried away by water movements. They are most active in spring and summer, a warm period when plankton is abundant.

Reproduction. Sexes are generally separate (gonochoric fish). However, there are cases where female fishes become male (protogynous hermaphroditism). Reproduction takes place in open water in spring (April-June) and the eggs and larvae are planktonic. At the end of summer, the juveniles return to shallow rocky bottoms and seagrass beds.

It is an opportunistic omnivore, capturing zooplankton, larvae, eggs, small crustaceans, or even grazing on sessile benthos (small animals or algae). Saddled seabreams often follow the swimmer very closely… undoubtedly looking for small preys carried away by water movements. They are most active in spring and summer, a warm period when plankton is abundant.The sexes are generally separate (gonochoric fish). However, there are cases where female fishes become male (protogynous hermaphroditism). Reproduction takes place in open water in spring (April-June) and the eggs and larvae are planktonic. At the end of summer, the juveniles return to shallow rocky bottoms and seagrass beds.

Geographical distribution. Mediterranean, southern Black Sea, eastern coasts of the Atlantic (from Angola to the southern Bay of Biscay, and in the islands of Madeira, Cape Verde and the Canary Islands).

The Damselfish, Chromis chromis (Linneaus, 1758) – Pomacentridae

Adults (size: 10-12 cm) are dark gray to black or brown, with flank scales having a lighter central spot. The caudal fin is typical, forked in the shape of a “swallow’s tail”.

They often live in schools in the first 30 meters of depth. Within these schools, fish coordinate their movements, simultaneously diving to the bottom when disturbed and returning to the surface when confident. In winter, they can migrate up to 50 m deep to find warmer temperatures (12-13°C).

The main food is plankton (zooplankton, fish eggs, small crustaceans) but they sometimes graze on tunicates or sponges on the bottom.

Reproduction. Sexes are separate (gonochoric fish). Reproduction takes place in summer, from June to August. The male exhibits then a particular behaviour: it clears a surface of rock (or sand) which becomes his territory. By jerky swimming, it attracts a female, encouraging her to lay her eggs. After fertilization, the female leaves the place, but the eggs are vigorously guarded by the male until hatching (the male protects and ensures their oxygenation by fanning it with his fins).

Below pictures illustrate adults coming together during mating

During the breeding season, fish stay close to the bottom and become territorial, nervous, and even aggressive when approached. Early June, I observed them occupying cavities and overhangs. Depending on their size, the cavities are occupied by one or more pairs.

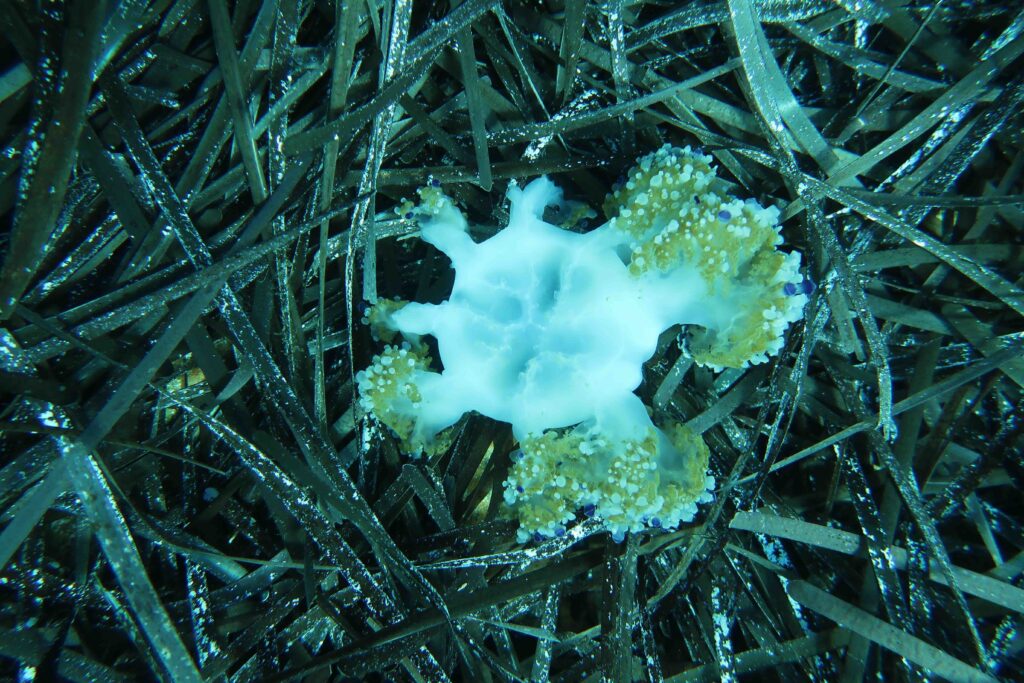

Young ones (15 mm) have a bright iridescent blue color; they live in small groups under overhangs and in rock crevices. At the end of summer, their size reaches 3 to 4 cm in length and their color becomes that of adults.

Blue iridescent juveniles swimming above a sponge next to two sea slugs.

Geographical distribution: Mediterranean and Eastern Atlantic (from Angola to Portugal, via the Azores, Madeira and the Canary Islands).

2. ENCOUNTER WITH LARGE SCHOOLS OF FISH

Sand smelts and sardines

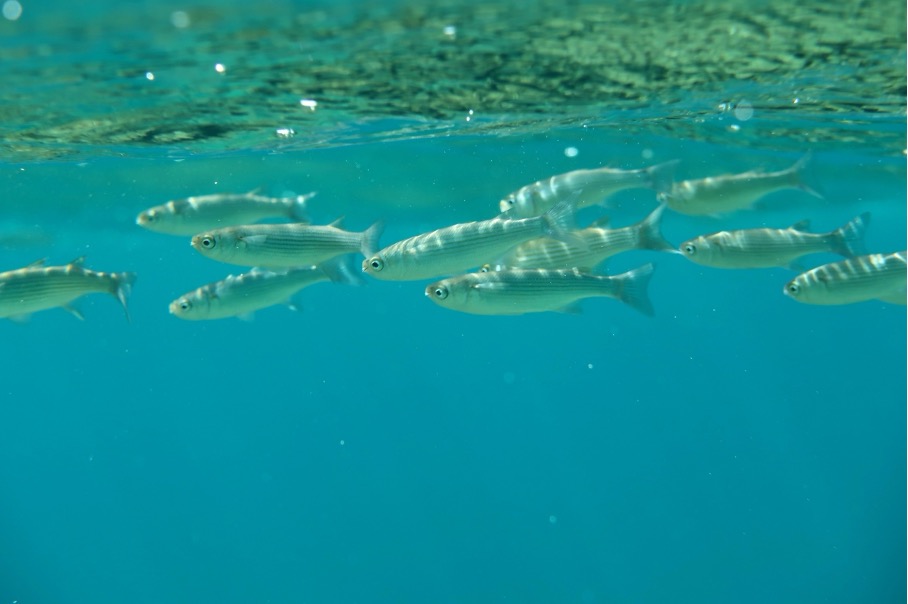

At the end of spring, it is common to find yourself in the middle of thousands of small fish swimming frantically in very dense schools. Observed here are sand smelts (Atherina) and sardines (Sardina).

Their behavior makes them easy to recognize: the movements of the sand smelts are jerky, alternating relative immobility and movement, while the sardines swim constantly… All these fish feed on zooplankton (sand smelts may also consume small prey such as crustaceans, worms, etc...). As preys to many predators (fish and birds), they are an important link in the food chain between zooplankton and predators.

Simple morphological criteria to distinguish sand smelts from sardines:

(1) Size: the body length of sand smelts is shorter (usually 10 cm or less) than that of sardines (10 to 15 cm for coastal schools, up to 25 cm in offshore schools)

(2) Number of dorsal fins: two for sand smelts and one for sardines

(3) Color: sand smelts have a horizontal silvery band/line on each side, while sardines have a green, sometimes bluish, back with well-marked iridescent patterns, a lighter silvery belly.

Sand smelts - Atherinae

There are several species of Atherina in the Mediterranean: Atherina boyeri (Risso 1810), Atherina hepsetus (Linnaeus 1758), Atherina punctata (Trabelsi et al. 2002), Atherina presbyter (Cuvier, 1829). The ones I encountered in Antiparos are Atherina boyeri, and probably… Atherina hepsetus.

Geographic distributions. A. boyeri is a common species in the Mediterranean, Black Sea, Eastern Atlantic (English Channel, North Sea, Bay of Biscay, Spain, Portugal to Mauritania, Madeira Island). A. hepsetus lives in the Mediterranean and the Eastern Atlantic (from Spain to Morocco, Canary Islands and Madeira).

Reproduction. Both species are gonochoric (separate sexes) without sexual dimorphism, their breeding period varies according to the geographical region; it takes place in spring in the south and east of the Mediterranean. External fertilization, eggs provided with sticky filaments which attach them to different substrates (rocks, algae, Posidonia, grains of sand), planktonic larvae.

The Big-scale sand smelt, Atherina boyeri (Risso, 1810)

Back (greenish brown, speckled with black) more pigmented than the belly which is silvery. Flanks with a bright golden or greenish horizontal line. Short rounded head, large, anterior eyes, protractile terminal mouth. Size 7-10 cm in length.

I observed A. boyeri while diving in a shallow, calm area, a sort of lagoon protected by a ring of rocks (with lots of algae on the rocks and seagrass beds in the pockets of sand in the middle of the lagoon) … the fish were regularly motionless on the bottom, isolated or in small groups. It is an euryhaline and eurythermal species, present in coastal lagoons, estuaries, sometimes in fresh water. It also lives in sheltered, shallow coastal marine areas (0 – 3 meters), with rocky or sandy detrital bottoms and seagrass beds.

The Mediterranean sand smelt, Atherina hepsetus (Linnaeus 1758)

Silvery belly and greenish to bluish back. Blue spots bordered with white aligned in the middle of each flank. Slightly pointed head with terminal mouth and large eyes. Size: 10 – 15 cm in length. The identification is less certain … the fish I observed were always very active, in very dense schools, a few meters deep and sometimes just below the surface.

Sardines, Sardina pilchardus (Walbaum 1792) – Clupeidae

A morning of May, South of Antiparos, in a quite rough sea (current and waves), I met impressive schools of sardines hiding the bottom as they were so dense. The fish (size ca. 15 cm) were swimming actively and very coordinated.

They have green back, sometimes bluish, with iridescent patterns on the back, lighter silver belly, a pointed head and fusiform body.

This pelagic fish approaches the coasts at the end of spring and remains there until autumn. In winter, sardines return to the open sea and to deeper water (up to 100 m). They also exhibit a diurnal vertical migration, moving in depth during the day and back to the surface at night.

Reproduction occurs from October to June, mainly in coastal waters. Fertilization is external with eggs and larvae occurring in open water.

Geographic distribution. Sardina pilchardus (Walbaum 1792) is the common sardine, present in the Mediterranean but also in the Eastern Atlantic (from Iceland and Norway to Senegal).

3. DISCREET SCHOOLS OF FISH

The thick lip grey mullet, Chelon labrosus (Risso, 1827) – Mugilidae

I observed them just below the surface or along algae-covered rocks; they were individuals about 20 to 30 cm long (but the maximum known size for the species is 80 cm).

It is a robust fish, with an elongated quite massive body, silver-gray in colour (the sides with 7 to 9 more or less marked horizontal lines). The head is very characteristic, flattened dorsoventrally with large prominent eyes and an upper lip with several rows of papillae. The two dorsal fins are short and triangular, positioned rather posteriorly. The caudal fin and its peduncle are wide and muscular, allowing rapid acceleration or even jumps of several meters out of the water.

Coastal species but found beyond the continental shelf during the cold season. Can swim upstream (euryhaline fish). It feeds on algae, diatom-rich mud, small invertebrates, … and fry or atherines.

Reproduction. Separate sexes (gonochoric fish), reproduction in winter, pelagic eggs and larvae; in spring, the fry return to the coast (see optimal food and temperatures).

Geographic distribution. Northeast Atlantic (Scandinavia and Iceland -> Senegal, Cape Verde, Mediterranean, Black Sea)

4. FISH THAT PASS STEALTHILY

The Pompano, golden pompano, derbio or silverfish, Trachynotus ovatus (Linnaeus, 1758) – Carangidae

I crossed T. ovatus very fleetingly, usually solitary or sometimes in pairs, at shallow depths (especially near sandy bottoms). However, offshore, it can live in schools.

It has a rigid, streamlined, oval-shaped body, laterally compressed, and silvery-gray in color (size: approximately 20-30 cm, but the species can reach 70 cm). The caudal fin is typical, scissor-shaped (heterocercal fin), with characteristic black tips. Two black spots also occur at the beginning of the dorsal and anal fins, which are translucent. These fins are symmetrical, beginning in the middle of the body and extending posteriorly to the caudal peduncle. The eyes are small, black, and anterior, close to the mouth. As a carnivore, it feeds on fish, small crustaceans, and mollusks.

Reproduction. Separate sexes (gonochoric fish). Spawning occurs in summer; eggs are pelagic.

Geographic distribution. Eastern Atlantic Ocean, Bay of Biscay, Mediterranean, Black Sea

5. PRETTY JELLYFISH

A few words to introduce jellyfish …

Jellyfish are not fishes! Large jellyfish as Pelagia noctiluca and Cotylozhiza tuberculata belong to the phylum Cnidaria, the subphylum Medusozoa, and the class Scyphozoa.

Jellyfish are observed in open water, pulsating rhythmically beneath the surface, carried by currents, or even washed ashore on beaches.

But… the ‘jellyfish’ is in fact a morphological stage within a somewhat complex life cycle! Indeed, a scyphozoan may have three successive living forms: (1) the medusa, which carries the gonads and releases the gametes; (2) the planula (released from a fertilized egg) is a ciliated larva a few millimeters long that swims to the bottom where it transforms into a polyp; (3) the polyp divides transversely, releasing young medusae (‘ephyra’). The sexes are generally separate (gonochoric animal).

Cnidarians include hydras, jellyfish, sea anemones, and corals. The phylum is almost exclusively marine (the few freshwater species are hydrozoans).

In cnidarians, the body has a radial symmetry (*), it is organized around a central oral-aboral axis and has only one orifice that serves as both mouth and anus! This orifice is surrounded by tentacles. Broadly speaking, the cnidarian body resembles a two layered bag: an endodermal gut-like cavity and, externally bordering this cavity, an ectodermal wall.

And… it’s the ectoderm that can be a problem for swimmers because this epithelium contains stinging cells, the cnidocytes! These cells (which gave cnidarians their name) allow to capture and immobilize prey (from plankton to fish) by injecting venom! They are very abundant in the ectoderm of the tentacles; each cell contains an apical vesicle full of venom and ending in a small harpoon coiled on itself. When a prey contacts the tentacle and therefore the cnidocyte, the harpoon is suddenly emitted outside at the top of the cell and penetrates the tissues of the prey or of a swimmer!

(*) It is interesting to point out that radial symmetry is common in sessile (fixed) animals and planktonic animals (like jellyfish), because it allows them to perceive the environment in all directions.

The luminescent jellyfish, the pink jellyfish, the mauve stinger , Pelagia noctiluca (Forsskal, 1775)

It is a nice, delicate jellyfish … but I don’t like too much to meet it! … Stings are sharply painful, often followed by itching and, in some cases, leaving marks (red lumps) on the skin. Some people may react severely (fever, allergies). This jellyfish can be present in abundance (as in September 2021). It luminesces during the night when disturbed by wave turbulence or by touching, hence its name ‘noctiluca’.

The bluish, translucent body is dotted with pink spots that protrude slightly from the animal’s surface. These spots more particularly gather many cnidocytes. The umbrella is shaped like a small dome (maximum diameter 17 cm). Beneath the umbrella, four festooned arms (maximum length 15 cm) surround the mouth (manubrium). Eight long, extendable tentacles are inserted along the edge of the umbrella… they can reach over a meter in length and thus float behind the animal! (see the two pictures below)

Cnidocytes present all over the body but particularly abundant on the arms and tentacles, allow to capture prey (crustaceans, ctenaria, jellyfish, salps, small fish). A veil of mucus brings the preys into the mouth. Digestion takes place in the gastric cavity, and what is not digested is eliminated through this same orifice. Occasionally, some juveniles fishes may occur under the umbrella.

Reproduction. Fertilization occurs in autumn. Jellyfish are either male or female (gonochoric animal). Gametes are released in the surrounding water, millions of spermatozoa by the male and thousands of eggs by the female (via its manubrium). A 20 cm diameter female may release up to 20000 eggs/day. Fecundation occurs in the water and a fecundated egg produces a planula larva, which in turn, transforms into small jellyfish (thus no polyp phase here). Pelagia noctiluca is referred to as a holoplanktonic jellyfish, i.e., one without a sessile stage. Juveniles are yellowish but become pinkish when adult. Life span is ca. 9 months.

Geographic distribution. Cosmopolitan, in warm and temperate water. Mediterranean, NE Atlantic (English Channel, North Sea), NW Atlantic, Caribbean, Indo-Pacific. It is an oceanic species that usually occurs in large swarms. When these are driven towards the shore, they cause massive stings among swimmers.

The fried-egg jellyfish, Cotylorhiza tuberculata (Macri, 1778)

What an astonishing encounter! The umbrella resembles a giant fried egg (its diameter can reach 40 cm). The center of the umbrella forms an orange dome while its periphery is pale yellow. Under the umbrella, the 8 arms extending the manubrium are subdivided into numerous densely packed tentacles whose ends form small purple or white discs.

As an adult, this jellyfish no longer has a ‘mouth’ in the center of the manubrium; it disappears during development of the juveniles through the fusion of the arms of the manubrium. But a multitude of pores, in fact small ‘secondary mouths’, are present on the tentacles! These pores connect the gastric cavity which extends into all the tentacles with the external environment. It is through these pores that the jellyfish ingest microplankton (diatoms, ciliates, copepods, mollusk larvae, etc.) and particulate organic matter.

C. tuberculata lives in symbiosis (mutualism) with zooxanthellae. These symbiotic algae are settled in the wall of the gastric cavity and more particularly at the ends of the tentacles where they benefit from shelter and good exposure to light. These algae give a violet to mauve color to the ends of the tentacles, and more particularly, to the distal discs (these ends are white in the absence of algae). Through photosynthesis, zooxanthellae contribute to the nutrition of their host. This dual food source likely explains the rapid growth of jellyfish (lifespan 6 months, maximum size 30-40 cm). Mild winters and hot summers are conducive to the massive development of C. tuberculata.

Juvenile fish, such as Boops boops (photo here above), amberjacks (Seriola sp.), and Hyperiidae copepods, may find shelter under the umbrella.

Reproduction. The life cycle is annual. The lifespan of the jellyfish is ca. 6 months, mature jellyfish occurring from June to September. The polyp phase lasts the rest of the year. The sexes are separate (gonochoric animals). Male jellyfish release their gametes in open water, fertilization and embryonic development take place into ‘brood carrying filaments’ occuring in females (sexual dimorphism). The ciliated larva (planula) leaves the female jellyfish and attaches itself to the bottom where it transforms into a small polyp (< 1 cm). Planulae are generally released from late summer to autumn. The following spring, the polyp splits horizontally (strobilation) into a series of small medusae (the ephyrules) that mature into adults within a few weeks. However, the polyp phase can persist as long as environmental conditions are unfavorable; it then feeds like a sea anemone, capturing small prey with its tentacles. Zooxanthellae are present in the polyps.

Geographic distribution. Endemic to the Mediterranean, especially in its eastern part (Aegean Sea, Adriatic Sea, Sea of Marmara, etc.). It can form large schools carried by currents offshore but also towards the coast.

C. tuberculata can be killed by waves or currents forcing them onto rocks, and by boat propellers (see below, a photo taken in September 2021, near to the bay of Aghios Georgios). They can also be preyed by seabirds (Laridae), sea turtles, and even be nibbled at by some fish such as the sea bream Diplodus annularis.

6. ENCOUNTERING SEA TURTLES

Sea Turtles (class Reptilia, order Testudines) belong to two families (the Cheloniidae and the Dermochelyidae) and count seven species.

Cheloniidae – 6 species: Caretta caretta (Loggerhead turtle), Chelonia mydas (GreenTurtle), Eretmochelys imbricata (Hawksbill Turtle), Lepidochelys olivacea (Olive Ridley Turtle), Lepidochelys kempii (Kemp’s Ridley Turtle), Natator depressus (Flatback Turtle).

Dermochelyidae – 1 species: Dermochelys coriacea (Leatherback Turtle)

Six species occur in the Mediterranean. The most common is the loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta), followed by the green turtle (Chelonia mydas), and the leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea, *). The last three species were rarely observed, namely, the Kemp’s ridley turtle (Lepidochelys kempii), the hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) and the olive ridley turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea). Only, two species, the loggerhead turtle and the green turtle are reported to breed in the Mediterranean (Eastern area mainly).

(*) Dermochelys coriacea, is the largest sea turtle (body length up to 2 m and weight up to 600 kg!).

Sea-turtles navigate over thousands km, they travel the offshore waters for years, finding their way to feeding places or to precise nesting beaches. Group of several hundred individuals can travel considerable distances from their living area to reach their nesting sites.

Chemosensory information plays a role in guiding their navigation. Youngs may drift with the current from their hatching beach. The odour plume emitted by this site will allow female adults to find back their birth beach to lay their eggs (they swim upstream following an odour gradient). The Earth magnetic field also provides directional information, allowing the animal to orientate latitudinally.

The loggerhead turtle, Caretta caretta (Linnaeus 1758) – Cheloniidae

The four following pictures were taken in July 2015 – South of Kato Fyra (Canon digital camera IXUS 850 IS). The sea turtle (ca. 50 cm long) was staying close for a long time, swimming peacefully over the bottom (3-4 m deep) and from time to time towards the surface. I was motionless for 10 min, and the turtle seemingly ignored me. The white ‘spots’ on the carapace are barnacles.

Description. The average length of fully grown individuals is 90 cm (ca. 135 kg). The loggerhead is the largest species in the family Cheloniidae (weight up to 400 kg). The colour of the carapace is brown greyish; the head is light brown with well-marked scales, bordered by a whitish skin. The plastron is clearer, usually light brown to yellowish.

The shell of the turtle encompasses a dorsal slightly bulged carapace and a relatively flat ventral plastron. Carapace and plastron are laterally attached to each other (bridge), leaving an anterior and a posterior opening (passage for the head, the limbs and the tail). The carapace consists of dermal bones covered by horny scales of epidermal origin. The bones of the carapace do not coincide with the scales. (The vertebral column and the vertebra are attached to the carapace inner side).

The carapace is covered by 11 to 12 pairs of large scales (scutes). There are 5 vertebral scales (along the middle of the carapace), and 5 pairs of costal (pleural) scales on each side. Smaller peripheral scales (about 25) border the whole carapace (the one posterior to the head is the cervical scale, surmounting the nuchal dermal bone). The plastron is covered by 6 pairs of scutes of dermal origin.

The head is large and harbors 2 pairs of prefrontal scales, the mouth lacks teeth but the jaws bones are covered with a horny strong beak.

The forelimbs are large and modified for swimming (sort of flippers), the hind limbs and the tail act as rudders.

Behavior. Mainly active during the day, regularly resting on the bottom, then with forelimbs extended laterally, with their eyes open or half-closed. Usual duration of dive is 15 to 30 minutes, but they can stay submerged for longer times (4h). Only female can leave the sea for the beaches when they are ready to lay eggs.

Food. The loggerhead turtle consumes a wide variety of food: mollusks (gastropods, bivalves, cephalopods), crustaceans (crabs, cirripeds, isopods), sponges, cnidarians (corals, sea anemones, sea pens, scyphozoans), bryozoans, brachiopods, echinoderms (echinoids, holothurians, asteroids), fish, and even young turtles, and, also algae, plants. It uses prominent scales at the tip of their anterior legs to maintain or to rip food, and its powerful inferior jaw to cut and crush the preys.

Reproduction. Adults originate from the Mediterranean Sea or from the Atlantic Ocean (for some of them). Female first breed when 17 to 33 years old. The reproductive period lasts up to six weeks. Mating takes place far from the nesting place. In the Mediterranean Sea, mating usually occurs from late March to early June and nesting, in June and July. A female lays 90 – 150 eggs on the same beach where it was born or a beach nearby. It will dig a nest in the sand, lay its eggs and refill the nest with sand, all this by through coordinate movements of the forelimbs and hindlimbs. The female then stop reproduction for two to three years. Eggs incubation lasts for approximately 50 days. The hatchlings dig the sand to emerge at the surface of the beach; they have then to reach the sea as fast as possible because of predators. Hatching often occurs at night (a way to escape predators and warm temperatures), moonlight and sky reflection on the sea surface guide the young to the sea.

At Agios Georgios (West side), September 2025 – depth: 2-3 m

At Agios Georgios (West side), September 2025 – depth 2-3 m

The three following pictures were taken at Agios Georgios (East side, facing Cape Koutsouros), in July 2003 (NIKONOS II film camera). The sea turtle (80-90 cm long) was resting on the bottom at a depth of ca. 6 – 7 m. Several minutes later, when I left the place, it was still there .

Geographic distribution: Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Oceans, and the Mediterranean Sea.

Loggerhead and green turtle are the only ones to breed in the Mediterranean (Eastern part mainly). For the loggerhead turtle, the nesting sites are mainly located along the coasts of Greece, but also of Turkey, Libya, Tunisia, Cyprus and Sicily.

Sea-turtles are vulnerable to extinction, they have a slow rate of growth, they reach their sexual maturity late, they don’t reproduce every year and, hatchling turtles and juveniles are preys of many predators. In addition, sea-turtles travel through seas and oceans that are occupied and overexploited by humans, meeting thus new dangers (e.g., they are accidentally caught in nets or killed on purpose for their flesh, they ingest plastics that mimic jellyfish prey etc… ).

Greek organizations concerned by sea-turtles protection and marine conservation are raising public awareness. See for instance:

https://naxoswildlifeprotection.com

https://archelon.gr/en/support-us/found-a-turtle?mid=1&mid2=25